I asked Proton’s Lumo AI tool about how authoritarian capitalism destroys political democracies.

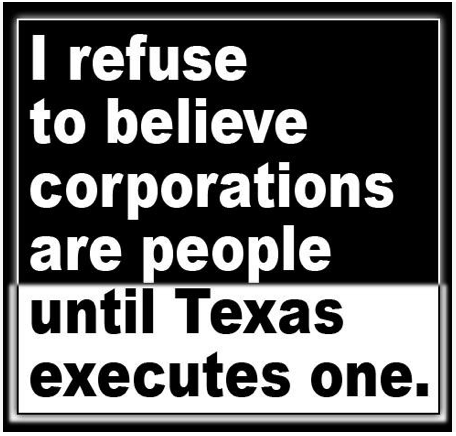

Don’t authoritarian economic systems like slavery, feudalism and capitalism, that concentrate wealth, tend to destroy coexisting democratic political systems that distribute wealth?

Short answer:

Authoritarian?oriented economic arrangements—whether they take the form of outright slave labor, feudal land tenure, or a highly concentrated market?capitalist elite—tend to undermine democratic institutions that aim to spread political power and economic opportunity. The mechanism isn’t inevitable, but history shows a strong correlation: when wealth and productive assets are tightly locked in the hands of a small ruling class, the incentives and capacities to preserve broad?based democratic participation are weakened.

1. Why concentration of wealth matters for democracy

Democratic principle What concentration of wealth threatens Political equality (one person, one vote) Wealthy elites can finance campaigns, lobby, and shape media, giving them outsized influence over policy and public opinion. Civil liberties (freedom of speech, assembly) Economic dependence on a patron class makes dissent risky; employers or landlords can punish activists. Rule of law (impartial courts) Powerful owners can capture judges, prosecutors, or law?enforcement agencies, turning the legal system into a tool of the elite. Inclusive participation (access to education, health, information) Concentrated wealth reduces public investment in universal services, creating a citizenry that lacks the resources to engage fully in politics. When a small group controls the bulk of productive resources, it can buy political influence, shape institutions, and suppress challenges to its dominance—processes that erode the democratic “distribution” of power.

2. Historical illustrations

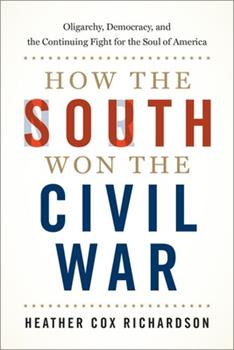

System Core economic feature Democratic impact Slavery (e.g., Antebellum South, ancient Rome) Forced labor owned by a planter/aristocratic class; wealth tied to human property. Political power was formally limited to slave?owners; any move toward universal suffrage threatened the plantation economy, prompting violent defense of the status quo (e.g., secession, Jim Crow). Feudalism (medieval Europe, Tokugawa Japan) Land ownership and serf labor bound to a hereditary aristocracy; peasants owed labor and tribute. Governance was decentralized but hierarchical; the monarch?noble alliance kept peasants politically powerless. When bourgeois merchants demanded representation (e.g., English Parliament, French Estates?General), nobles resisted to protect their landed income, leading to revolts and eventual transition. Concentrated Capitalism (late?19th?century Gilded Age, modern oligarchic economies) Ownership of factories, finance, tech platforms rests with a tiny elite; wealth accumulation outpaces wage growth. Campaign finance, lobbying, and media ownership allow the elite to shape policy (tax cuts, deregulation) that reinforce their advantage, while populist reforms (progressive taxation, universal health) face organized opposition. Democratic backsliding often follows when the elite perceive redistribution as an existential threat (e.g., corporate?funded voter?ID laws, gerrymandering). These cases share a feedback loop: economic concentration fuels political capture, which in turn creates policies that preserve or deepen that concentration.

3. Mechanisms that link economic concentration to democratic erosion

- Patronage networks – Wealthy owners fund clientelist relationships (jobs, contracts, welfare) that bind citizens to the elite and discourage collective action.

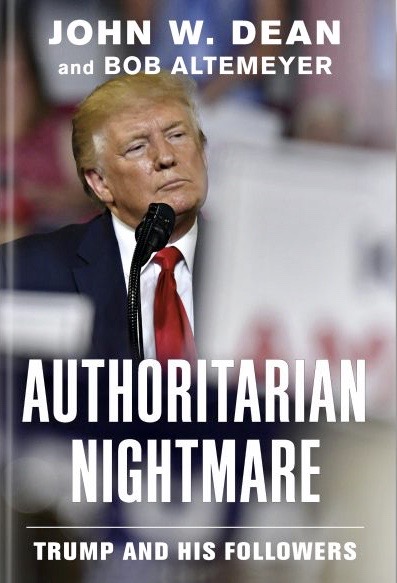

- Media control – Ownership of news outlets lets the elite set agendas, marginalize dissent, and manufacture consent.

- Legal capture – Funding of think?tanks, law firms, and judicial appointments enables the wealthy to shape the interpretation of laws to protect property rights over egalitarian reforms.

- Economic coercion – Threats of layoffs, eviction, or loss of credit can silence opposition, especially in economies lacking strong labor protections.

- Ideological framing – Narratives that equate “wealth redistribution” with “class war” or “government overreach” create cultural resistance to democratic reforms.

4. Counterexamples & Nuance

Example Why democracy survived or improved despite concentration Post?World War?II Western Europe Strong labor movements, social?democratic parties, and progressive taxation redistributed wealth while preserving market economies. Institutional safeguards (independent central banks, strong unions) prevented oligarchic capture. Singapore Highly centralized, meritocratic government with limited political competition, yet achieved rapid development and relatively low corruption. Critics argue it trades political pluralism for economic efficiency. United States (mid?20th?c.) Despite rising corporate power, New Deal reforms, civil?rights legislation, and a vibrant civil?society expanded democratic participation and reduced extreme inequality. These illustrate that institutional design matters: robust checks (independent courts, free press, strong civil society) can buffer democracy against the corrosive effects of wealth concentration. Conversely, weak institutions accelerate democratic decay.

5. Theoretical lenses

Lens Core insight on wealth?concentration vs. democracy Marxist Economic base determines superstructure; when the mode of production concentrates surplus in a ruling class, the political superstructure (law, state) reflects that class’s interests, limiting genuine democracy. Schumpeterian Democracy is a competitive marketplace of ideas; if market power translates into political market power, competition is distorted, undermining the “competition?driven” model of democracy. Acemoglu & Robinson (inclusive vs. extractive institutions) Inclusive economic institutions (secure property rights for many, open markets) foster inclusive political institutions; extractive economic institutions (slave labor, feudal dues, monopoly capitalism) produce extractive political institutions that restrict participation. Olson’s “Collective Action” Small, concentrated interest groups (oligarchs) can organize efficiently to lobby for favorable policies, whereas dispersed citizens face high coordination costs, leading to policy bias toward the elite. All four converge on the idea that when economic power is highly concentrated, the incentives and capacity to sustain broad?based democratic governance diminish.

6. Practical takeaways

- Strengthen redistributive mechanisms – Progressive taxation, universal health/education, and robust social safety nets reduce the economic leverage of a narrow elite.

- Protect institutional independence – Safeguard the judiciary, electoral commissions, and regulatory agencies from capture by wealthy interests.

- Promote media pluralism – Antitrust enforcement in the communications sector and public broadcasting can counteract elite media monopolies.

- Empower collective bargaining – Strong labor unions and worker cooperatives give the many a coordinated voice that can balance elite lobbying.

- Enhance transparency – Campaign?finance disclosure, lobbying registries, and open?data initiatives expose the flow of money into politics, allowing citizens to hold power?brokers accountable.

Bottom line

Authoritarian?styled economic systems—whether they rely on enslaved labor, feudal obligations, or ultra?concentrated capitalist ownership—tend to erode democratic institutions that aim to distribute political power and economic opportunity. The relationship isn’t deterministic; strong, inclusive institutions can mitigate the corrosive effects of wealth concentration. Nonetheless, history repeatedly shows that when economic power becomes the primary source of political influence, the democratic “distribution” of wealth and voice is jeopardized.